Stéphanie Latte Abdallah, Researcher at IREMAM (CNRS) Aix-en-Provence

Published in Issam Nassar and Rasha Salti (ed.), I would have Smiled. Photographing the Palestinian Refugee Experience (a tribute to Myrtle Winter-Chaumeny), Institute for Palestine Studies, 2009, p. 43-65.

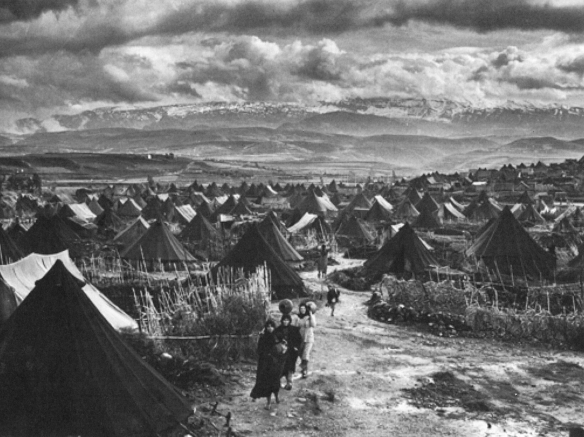

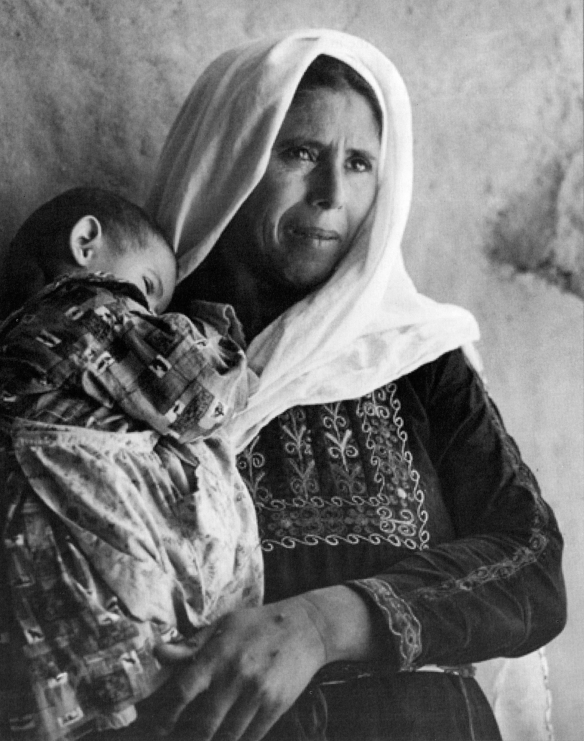

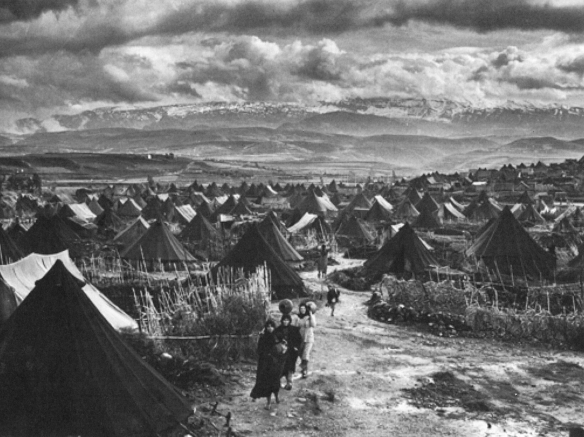

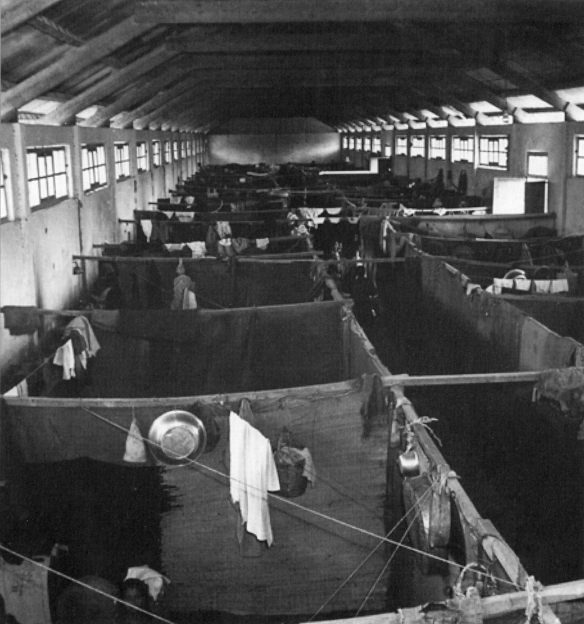

Naher al-Bared refugee camp, near Tripoli (Lebanon), 1952. Photo by Myrtle Winter-Chaumeny.

The establishment and the content of the photographic archive of UNRWA, and more broadly, of the audiovisual branch, are to be understood within the historical and political constraints that have shaped the Palestinian and refugee issues and UNRWA’s role, programs and activities since 1950. History and images are here more than ever inextricably linked, as the former has also been determined, to an extent, by the latter (1). At the same time, recent Palestinian history has also been the story of an ongoing struggle for historical visibility starting from a void, an absence (following the 1948 war and the creation of only one of the two states provided for in the 1947 United Nations Partition plan). From the denial of belonging to the land of Palestine of the first two decades—as expressed by the Zionist slogan “a land without people for a people without land” or Golda Meir’s statement in the 60’s, “Palestinians, who are they? They do not exist”—the Palestinians have gone through a slow process of presence within history. UNRWA’s humanitarian images display the specificity of the Palestinian refugee history, for they are the place and in a sense already the result of a political, cultural and historical confrontation on an international level.

UNRWA refugee images were firstly geared to document and publicize the programs of a humanitarian agency so as to increase donations (2) and, from this perspective, to record and document the refugees’ situations and events. They were first geared towards its financial backers—international organizations and the donor countries (and above all towards the major ones, which have been slightly changing over time but remained North American and European (3); and secondly, towards the UN, the local and international press, governments of the host countries of the refugees, refugees and UNRWA staff. Reception has thus been key in shaping the images.

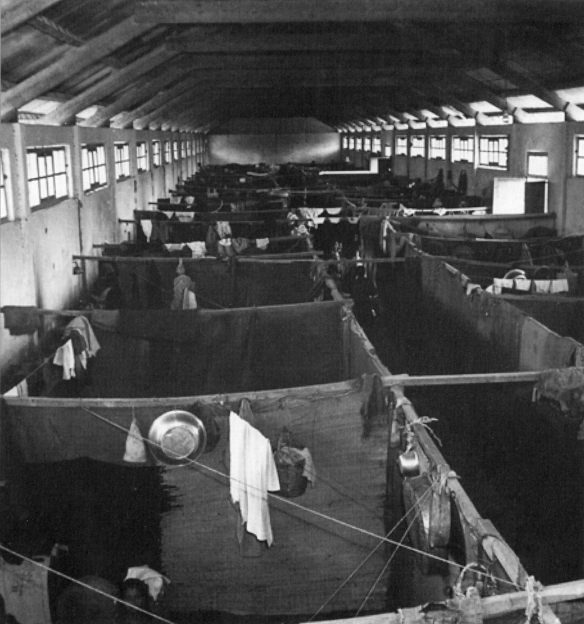

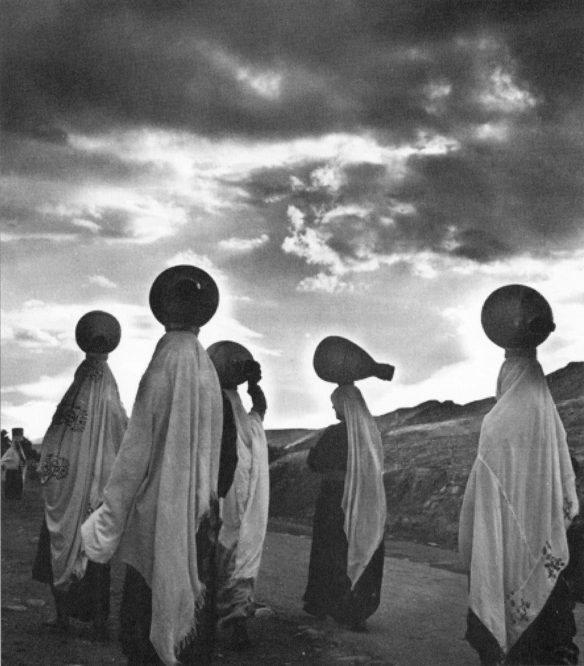

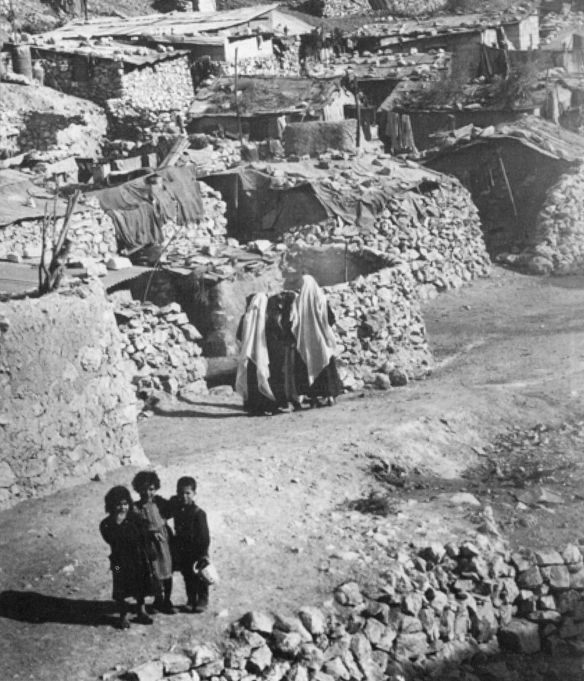

Mia Mia camp, near Sidon (Lebanon), 1952.

Institutional documents, photos and films made by UNRWA since its creation, in 1950, have indeed been submitted to a tight array of limitations especially until 1974, when the PLO was recognized as the representative of the Palestinian people, by the UN and by most countries around the world. From this point on, the PLO became an official interlocutor of the UNRWA, and began to have a say in its activities and public relations policy. With the 1967 war and the second exodus, UNRWA had started to widen its services to the overall Palestinian community. In the course of time, UNRWA was also progressively invested with the mission of protecting the Palestinian people during conflicts (e.g. at the beginning of Lebanese war in 1975 and later of the first Intifada in 1987), within the frame of international law. All this gradually and radically affected its images and public relations policy.

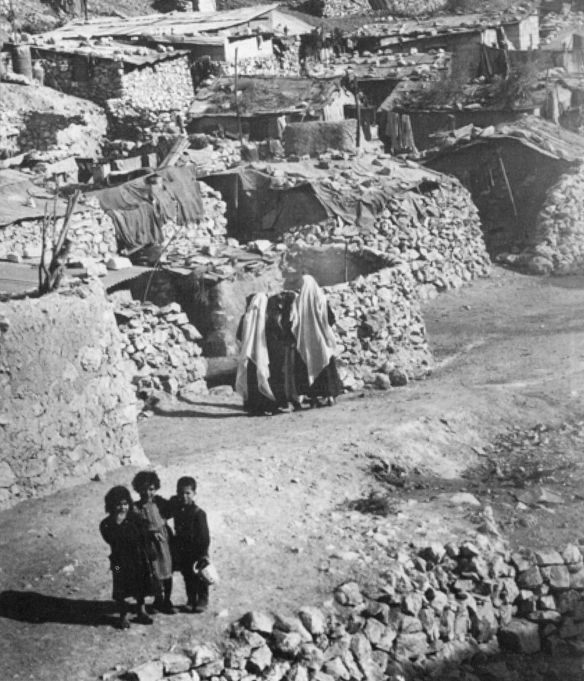

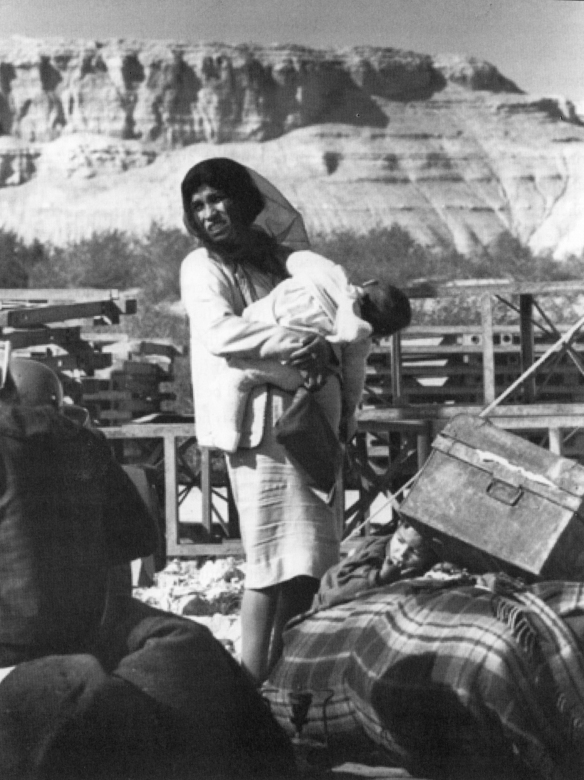

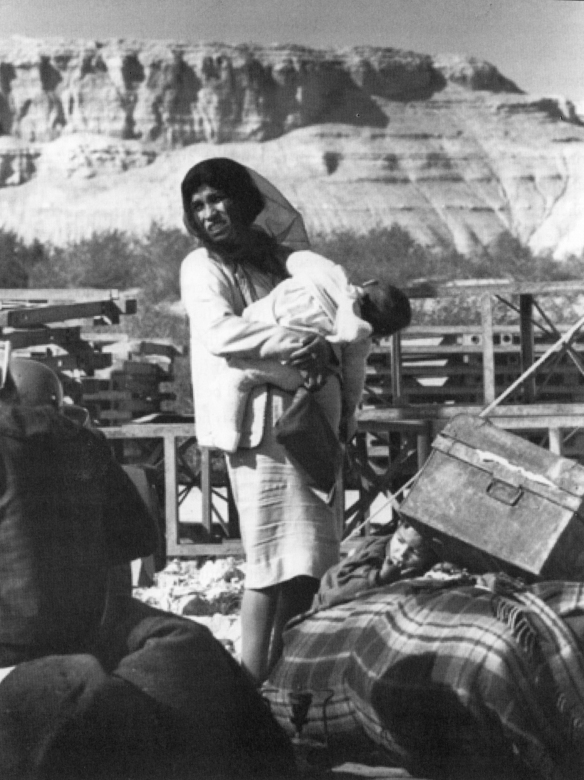

From Wadi Seer to Amman new camp (Jordan), 1959.

In this paper, I will focus on the first decades, and follow the first steps and moves of the Agency’s photographic and film production (1950-1978). If the 70’s and the 80’s are outstanding moments of change in UNRWA’s images and representations of the refugee issue, 1978 is an adequate year to mark a first period for the purpose of this paper: it corresponds to Myrtle’s winter retirement and to the relocation of the Agency in Vienna following the turmoil of the Lebanese civil war. UNRWA’s historical stills (4) are at the core of this short article but the main aim of the article is to give a few insights to understand them within a broader context—i.e., in relation with the constitution of the Agency’s audiovisual branch and in comparison with the films—and, above all, to discuss how they have mirrored the political struggle for visibility and/or documented refugee History.

Photography as an Act of Reality: Buildingthe Photo and Audiovisual Branch

Up until 1967, UNRWA’s stills, and above all, films were strongly shaped by the initial international will of isolating relief from politics—as it was instituted by the UN in December 1948 with the creation of the Conciliation Commission, on the one side, and of the UNRPR (a relief umbrella) on the other (5). Until 1950, the UNRPR coordinated the work of the Red Cross—the ICRC (6) in what was called Arab Palestine (West Bank) and the League of the National Societies of the Red Cross in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon—and of the Quakers (American Friends Service Committee) in the Gaza strip. The Quakers had from the beginning a different role and a mediating and political mission. They did not comply with this separation, as shown on the images they produced—their unique mute film and their stills. Such images contrast sharply with the images of the Red Cross and later of UNRWA—until 1967—which taken all together display coherent and recurrent representations on the land of Palestine and on the refugees.

Soon after the 1948 exodus, in 1949 and 1950, it was almost impossible to film or to take pictures of the situation in Palestine and even to document the plight of those who were then called the “Arab refugees”. A UN film maker, Mr Wagg, asked to come to Gaza by the Quakers to record their action faced great difficulties in this mission:

“He [Mr Wagg] reports that he is encountering very considerable resistance in the film division of the UN to his project because they are closely allied with groups particularly sympathetic to Israel, who are not very anxious to have the needs of the Arab refugees presented” (7).

This resistance implied a strong emphasis on isolating humanitarian images from what could be political or historical images. Writing to Stanton Griffis, head of UNRPR, Mr Evans, in charge of the Quaker mission, insisted on that point concerning a UN photographic report on the refugees’ conditions in the Gaza strip aimed at fundraising. The fighting was then still going on: “He also photographed bomb damage in the town. I made a point of avoiding all photography and activity indicating interest in the military aspects of the affair, since my permission had been obtained on the basis of the refugee story only”, i.e. on photographs only showing the “need” and “relief operations” (8). As shown in the Red Cross and UNRWA films and pictures, politics was understood in a very broad sense because of the innate political nature of territorial belonging. These representations were indeed all together masking, or silencing, the historical conditions and the reality of a land conflict, its belligerents and stakes, and the social identity of the refugees prior to their exodus (9).

Refugee Camp in Gaza.

This position has been reiterated throughout the 50’s and the 60’s: “During the 60’s” explains M. Z. in charge of one of the Public Information Office of UNRWA, “the political environment did not allow to call things by their names” (10). “We could not say” mentions M. N., a former UNRWA photographer, “for instance the Allenby bridge or the Karameh camp has been shelled by the Israelis”, we had to say “it has been bombed”. Because we were UN and a humanitarian agency. We were supposed to help the refugees not say who did that” (11). And this has been the case till Giorgio Giacomelli became Commissioner general (1985-1991), when UNRWA ’s mandate and the international political environment had changed and when the head of the Agency was giving an increased attention to film and photo production:

“In the 80’s it was a great period. We cannot say that there was a real policy or a communication concerted line and consciousness but Giorgio Giacomelli was supporting film production, [he] wanted things to be called by their names and was more committed. It has to be said that it was the time of the violent invasion of Lebanon by the Israelis. It is a turning point in UNRWA films.” (12)

Until that time, though many breakthroughs in the former representations and policy had already been made from within triggering the slow process of change, the main concern was material limitations and the necessity to find the means to “maintain the audiovisual department alive, which was already not an easy thing. We had scarce means. Nobody like[d] UNRWA. It was set up to keep Palestinians calm, so there is a real and big battle around UNRWA and its films.” (13)

Building from scratch a photo section and an audiovisual branch, which could later on subvert its initial limitations to document historical events more accurately, was a major challenge, an innovative project and a political action. This enterprise owes a lot to Myrtle Winter who, since 1954, headed the small photo section—part of the Education Department—created by Alexander Shaw from UNESCO in 1950, in UNRWA HQ, in Beirut. He selected a group of talented Palestinian refugees young men and sent them to Cairo for a few months to be trained as film makers and script writers. Aside from the pictures, the photo section produced few documentaries and educational film strips. From 1954 onwards, the photo section’s staff started to grow and reached more than 20 persons in 1978. “She [Myrtle Winter] had power within UNRWA, she was very strong”, remembers S. H. former script writer, “she knew how to make projects succeed. It is thanks to her that there had been money to make cinema and develop the audiovisual at UNRWA. She started it all.” (14)

This Office held three sections (Still photo, Filming and Art Design) and, in the 60’s, became a wider Audiovisual Branch Office (one of the three sections of the Public Information Office which comprised also the Publication Branch and the Translation Branch) when the film production started developing rapidly. In a context of historical invisibility of the refugees and mythification of the 1948 war history by the Israeli official historiography of that period (15), the numerous stills taken by Myrtle Winter and the photographers of the UNRWA Photo section were strong “certificate[s] of presence” (16). The specificity of photography is indeed, if we follow Roland Barthes, to “ratify what it represents” (17). It is not to remember the past but to be an “emanation of a past reality” (18). It poses, more than any other art, “an immediate presence to the world—a co-presence”. It poses a presence which is “not only political (‘to participate by the image in contemporary events’)” but “is also metaphysical.” (19)

On the Photographs Seen through the Films

Up until 1967, most of the humanitarian images show recurrent representations which display what I will call, using Roland Barthes’ words, a naturalization of refugee history (20). I will only mention some of them briefly here (21). Les errants de Palestine (22), Sands of Sorrow (23) or the UNRWA films of the 60’s display a total rupture between the ongoing situation of the refugees and their previous life. Humanitarian agencies seem to be intervening as if the exodus was the starting point of the history of the persons, on a tabula rasa. Refugees are thus presented as eternal wanderers, without roots, as poor people, passive and sometimes even idle. A refugee identity is thus created which takes the place of any other social identity (such as that of a peasant, or a person with a home, engaging in social and economic activities, etc.) as doing otherwise would have immediately been construed as a political act, in so far as it is related to the land. The conflict having been silenced, the refugees are represented as victims of an unknown disaster, which could even be a natural one. The view on the land of Palestine, as the Holy Land, serves just too well this negation of history. A land, where Christian traces and references are dominant, but not exclusive as most of the films insist on a syncretic image of the land of Palestine, the birthplace of the three monotheisms. The land is then presented as saturated with monuments and archeological vestiges, and also as a place of recurrent, though unexplained, conflicts among which 1948 has no specific history (24). The historical narration is erased and replaced by a mythic representation of time. In most of these productions, the subject’s presentation is similar: biblical times come first, then ancient civilizations or archeology, and sometimes the Crusades. These pre-67 UNRWA films seemingly go, from showing a number of monuments, to showing the consequences of the last conflict; the plight of the “Arab refugees”. Constant backs and forth leaps are made between a mythical time and the contemporary daily life of the refugees (25). At the beginning of the 60’s, the new education programs of UNRWA—more consensual than previous ones in that they were mostly oriented towards resettlement in the host countries)—stimulated investment in film production, in order for the institution to market a new and positive image of the refugees. Most of the films of the 60’s then centered around the education and training of the refugees, so that the inactivity of refugees stopped being essentialized. Rather, it becomes the result of a situation, which remains unexplained. The target is the second generation of Palestinian refugees born in the camps, whom UNRWA wants to offer the opportunity to change their own existence. Hence, the focus of the UNRWA films of the 60’s is put more on a positive representation of the refugees’ potential and on individual trajectories (26).

Mar Elias refugee camp in Beirut (Lebanon), 1966. Photograph by Jack Madvo.

Interestingly enough, the political and material constraints that shaped these productions had less of an impact on the stills than on the films. Aside from the Quakers’ images which are all contrasting with the main representations of the land of Palestine and of the refugees displayed by the pre-67 Red cross and UNRWA images (even their mute film) (27), the pictures of the Red Cross and of UNRWA offer a greater diversity than their films. The Red Cross stills even have an outstanding historical perspective as they documented events at an early period. Indeed, the Red Cross photographs widely show the 1948 mass exodus of the Palestinians on foot and by buses, and the places left. They also show population transfers between the Jewish and Arab zones during the war, bombings and exchanges of war prisoners. They clearly identify the belligerents and the progress of the conflict. Some pictures of the Deir Yassin massacre, forgotten in the written archives of the ICRC, were even taken and kept with the report of Jacques de Reynier in charge of the ICRC. They stand as early proofs and evidence testimonies on some war practices.

Khan Yunis camp (Gaza Strip).

This last example partly explains why films and stills contrast: because of their different purposes. Not all photos, and notably not the ICRC ones, were meant, as films were, as communication tools targeting an international audience for the purposes of fundraising. UNRWA films were made under close supervision and a strict protocol, where the director or the person shooting and producing the images was often not directly involved in the conception of the films ( though this changed overtime). Usually, the script would be written by a person especially appointed for that purpose and would have to be approved by the head of the audiovisual branch and by the Commissioner General’s Office (whose approval also had to be obtained for the final version of the film and its diffusion). The result is completely “controlled” documentaries which lack originality and/or creativity in their writing and shooting. As Jean-Paul Colleyn has stated, in most institutional films, attention is indeed concentrated more on content than on form:

“The cameraman seems to have the mission of shooting images meant to accompany a documentary text: most of the time, he films wide shots and the close-ups are either anecdotic either ‘sentimental’, as for example still shots portraits of children or elderly. In this mode of documentary production, (…), the image operator ignores the final editing his images will be submitted to. The cameraman’s role is coverage, he is not supposed to look for interactions or to shoot sequences.” (28)

This was certainly the case in UNRWA productions—all the more as many shots were used in different films, to illustrate distinct texts.

Aqabat Jabr refugee camp, Jericho (West Bank).

Moreover, up until the 80’s, the protagonists—the Palestinian refugees—are never interviewed, and either a voice over, that of the Agency, or that of the speaker’s—as is the case in A Journey to Understanding (1961)—is covering any other individuality. The gradual change in the representations of the refugees and of their history, which started in 1967, is reflected in the form of the productions. In Aftermath, for instance, a film on the 1967 exodus, displacements and conditions of the war are shown, and for the first time a Palestinian, an UNRWA employee, gives his views on the situation created by the arrival of the displaced in Amman. Since that time, the tragic consequences of the conflicts are recorded, starting with the Lebanese civil war (since 1975) and then the first Intifada (since 1987). Though the neutral position of the Agency implied striking a sharp balance and many redlines, refugee History and Palestinian people rights are at last mentioned (29). So are the UN resolutions and the evolution of the debate on the Palestinian issue at the UN or at the international level. Palestinian social and cultural identity (30), and Palestinian cultural traditions and heritage are widely displayed in line with the image driven by the national movement (31). But it is only with the first Intifada, as stated by the former film director at UNRWA, G.N., that

“I could have in my films more critical interviews, which were talking of Israeli practices and of the exodus of 1948 and 1967. I wanted to make interviews of persons, in their language, and not only add this voiceover which spoke in their place through a text that we wrote. They accepted that Palestinian refugees speak of their own experience, that we see things from their view. Giacomelli even urged us to go further. The first film I showed him, he told me ‘it is too shy, if people suffer then we have to see it on screen’. And at last, we had Betacam material.” (32)

Jericho 1967.

Contrary to what Barthes writes about cinema in general, UNRWA productions were so closed and monitored until 1967 that no off-camera, or “champ aveugle” (33) as he names it, could be imagined or perceived. A “champ aveugle” that, according to him, exist in photography only when a detail (called punctum) comes to break, contradicts, captures the attention from what is seen as the main subject. Some UNRWA stills do indeed leave more freedom of interpretation to the viewer, do not assign meanings as heavily as the films and have more evocative power. Some of them, even the ones that are similar to some shots of the films—as if they had been taken out of them—do carry the view and the viewer outside the frame. The themes of the pictures are, though, recurrent : the camps’ infrastructures and the tents ; the people, who are mainly elderly man or women, women and children; schools and health consultations, etc. They do not document historical events and, in some cases, even seem to blur history by erasing the context of the image, as I will consider in more details further on. Some of the photographs even look like engravings and give the impression of being inscribed in an eternal past.

Jisr el Basha Refugee Camp in the outskirts of Beirut, Lebanon, 1952. Photograph by Myrtle Winter-Chaumeny.

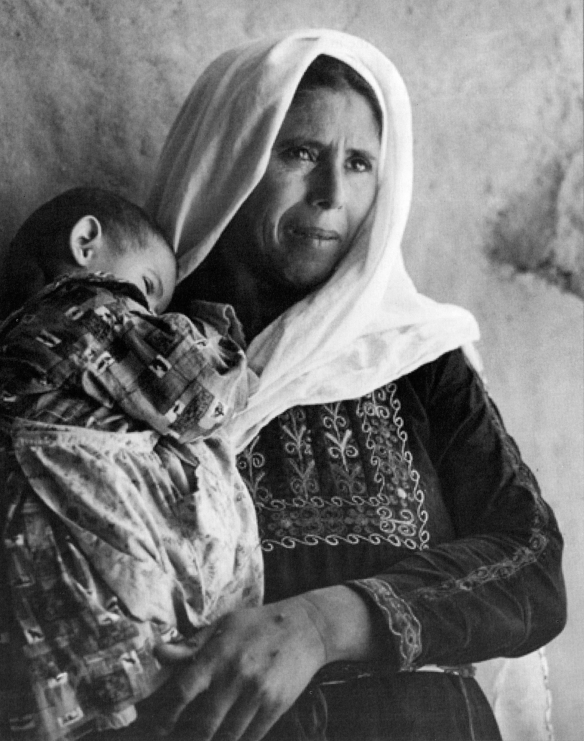

Up until 1967, the photos tend to “universalize” the refugees (34) in a way common to most humanitarian iconography, as described by Liisa Malkki. This representation of refugees is built on the “common assumption that ‘the refugee’—apparently stripped of the specificity of culture, place and history—is human in the most basic, elementary sense” (35). The numerous photos of women and children are archetypal of humanitarian images, where the figures embody the notion of displacement and the pure humanity that refugees are supposed to incarnate (36). Pictures of the elderly constitute a similar representation, all the more as they imply the quasi-absence of young or mature men on UNRWA photographs. Taken all together, most of UNRWA old photos shape the universal representation of a “human-victim” (37) deprived of any specific identity. This change in the representation of refugees, in relation to the overall perception of the same, took place during the 20th century. Indeed, this century witnessed a transformation from the European refugees of the first decades and of the beginning of the cold war period that were considered “political” refugees to a strictly humanitarian and universal understanding of the refugees from the constitution of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 1950 onwards. The effect of the change for the refugees that followed, most of whom originated from the South, has been an insistence on their destitution. Palestinians became refugees at this historical turning point of the creation of the UNHCR though they had not been included in its mandate.

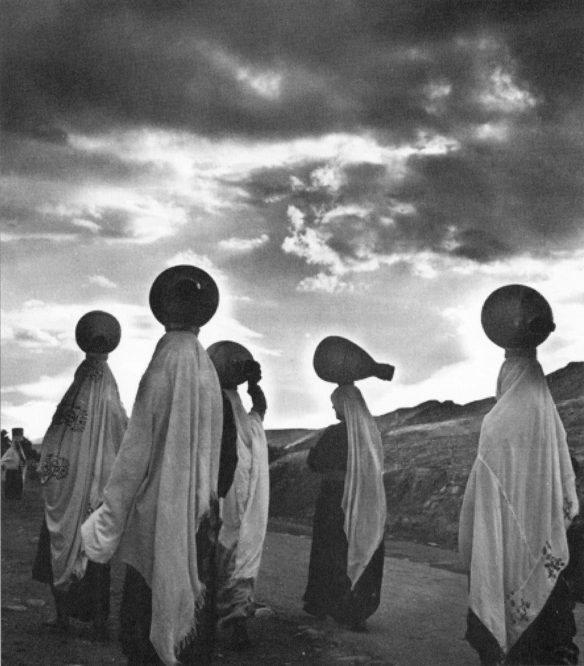

Exodus.

In spite of this, some of UNRWA’s photos defied the constraints by a certain artistic manner that expressed something more than what was on the frame, and that might have something to do with a view of time a representation of time, which Roland Barthes reads in some pictures and even more acutely in some historical photographs, which he calls “a pure representation of time”. He sees it as “another ‘punctum’ (another ‘stigmate’) beside the ‘detail’. This new punctum, is not one of form but of intensity.” (38)

History Blurred and Reinvented

What makes a photograph historical is, aside from the image itself, the date and title and/or caption which contribute to situate it and contextualize it. According to Barthes, for any picture, “the date is part of the photo: not because it conveys a style but because one cannot but notice the date, one can imagine life, death, the inexorable passing out of generations” (39). The name of the photographer could also be an important, though not a necessary, indication.

Continuing exodus (Jordan Valley).

Many photos taken before 1967 and even later do not carry any date, do not picture a historic event or do not carry a caption that could help determine its time and location. This is probably the result of UNRWA’s initial temporary mandate, added to a general political environment. During those years, there was hardly any awareness of the archives being built. From the key 1967 event onwards, a change can be noted: in contrast to the previous period, few photos are without date or appear blurring history insofar as events do enter into the frame and make the subject of numerous pictures. This is particularly clear in the many photographs of the 1967 exodus and the effects of the Lebanese civil war on Palestinian refugees and camps. Thanks to the captions—which are generally useful even if a few of them are inaccurate or too general—there is a way to figure out roughly when the photo was taken. Oftentimes, the dating is done in terms of historical periods defined by key historical events: the years following the 1948 exodus; before, during or after 1967—as the camps of Jericho were almost emptied after the second exodus; between 1967 and 1975—beginning of the Lebanese war and after, etc. The issue of date is also key as far as the films are concerned: indeed, some of them only carry the indication 1948-1950, pre-1967 or post-1967 and sometimes 1960’s, 1970’s, mid- 1970’s, or even 1980’s (40).

Dekwaneh Camp in Beirut (Lebanon), 1975-1976. Photo by Myrtle Winter-Chaumeny.

As shown in the UNRWA Photo Catalogue made at the beginning of the 80’s (41), the way the photos were classified in the archives—at least until the 1990’s—also tends to prevent a historical reading of the pictures and of the refugees’ situations. Indeed, the classification is closely linked to UNRWA ’s organizational division between the Relief and Social Services Department, the Education and the Health Department as they are grouped under four headings: Refugee living conditions (in which, amongst others, are pictures documenting the events of the exodus; the Lebanese civil war; and one of its more terrible moment for the Palestinians, the Sabra and Chatila massacre), Education for refugee children, Health Care and Arts and Crafts. In the 1990’s a complete reorganization of the audiovisual archives, and notably of the pictures, took place. Such reorganization implied a search for ways to date the photographs precisely, a new classification of the same, and the inclusion of the photographers’ name in most of them. This archive has gone through a process of contextualisation, re-inscription of history, a kind of reinvention.

Victims of the Lebanese civil war in Beirut (Lebanon), 1975-6. Photograph by Myrtle Winter-Chaumeny.

The organization of the website mirrors this new conception of the archives and of the role that photographs can play. So do the two big photo exhibitions put together on the occasion of the 45 and 50 years’ anniversaries of UNRWA (the former one called “The Long Journey” and the second one held in 2000). In “The Long Journey”, the main events of Palestinian and refugee history since 1922, (the starting date of the British mandate in Palestine) are recorded through photography using, from 1950 onwards, UNRWA photographs which are accurately dated, titled, and situated. The pictures presented in the website are also clearly contextualized, identified and dated and very often carry the name of their author. They are classified around three main sections (Photo archives, Recent photos and Fresh photos). As far as the archives ones are concerned, the new setting has added historical files, even though it is still linked to UNRWA’s evolving organizational structure (which now includes new key programs such as Micro-finance and Micro-enterprise). This new setting is thus divided into seven files: Refugee conditions; Exodus; Destruction; Education; Health; Micro-finance and Micro-enterprise; Geographical (mainly ancient history and archeological sites of the region). Some of these files are, in turn, subdivided into sub-files according to the different zones of operations (Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and Gaza). This reclassification has gone hand in hand with an increased interest in the audiovisual archives and in the place they occupy in Palestinian national history and memory. Symptomatic of this renewed interest is, for instance, the project to digitalize and store all the film material in good conditions.

The slow breakthrough of History in UNRWA photos, as well as in films, involved several steps: change of subjects, change of formal techniques and new, contextualized readings of the same images. Indeed, for the films, old material and shots were used in later films with a complete different purpose and often, this time, to serve a historical narration (e.g. Prelude to Peace, 1987). This move has been accompanied by the will to individualize the work of image and film makers. Up until the 1980’s, almost all films lacked detailed credits. As a result, it was impossible to know who wrote, filmed or directed them. We do know, however, that, at the time, Myrtle Winter was orchestrating the process and was behind the work of the team of the audiovisual Branch on these productions. Afterwards, filmmakers such as Georges Nehmeh began to be identified and so were the different key technicians. The recognition of the work of different photographers led to a greater sense of professionalism. Testimonies of this change were the clips made for CNN’s World Report (between 1989 and 1997) which reached a significantly larger audience. It also led to question the photographs in a more artistic way: not only as documents but also as individual testimonies on refugee History.

Here, the discrepancy between the photos and their intention is striking. Indeed, in most cases the aim was to give an account on living conditions, on habitat, infrastructures, services. The camps—with its tents, prefabricated structure, and its various shelters and houses—were central in these images. So was the way people coped, with the help of UNRWA, with their harsh environment and surroundings. In most of the images, though, the view remains distant, as if the people were completely alien to their place of living or to the landscape. This sense of distance stands in sharp contrast to the “territorial intimacy” described by Jean-François Chevrier (42) in Marc Pataut’s photographs of the inhabitants of Le Cornillon (the wasteland on which the Stade de France was built in St Denis, near Paris). Like Palestinian refugees in the camps, these people did not choose to be living in this improvised slum, but from the pictures their daily life in the wasteland can be felt which is in general not the case with UNRWA stills. In UNRWA photos, the separation and estrangement of the people from the places together with the lack of interaction between people or between them and the place conveys the impression of an absence of personal histories, of a disincarnated reality. This absence can be considered partly as an inner limit of photos taken under such political, institutional and material constraints by photographers who were beginning in the 50’s and 60’s as, for most of them, they learned their job taking pictures for UNRWA. It might also be partly understood as marks, traces of exile or as the perceptions of Palestinian exile that these photographers had (some being Palestinian refugees, some Lebanese or Europeans) and wanted to convey.

Endnotes:

(1) See Latte Abdallah, S., 2007, «Regards, visibilité historique et politique des images sur les réfugiés palestiniens depuis 1948», in Le Mouvement social n°219-220, Spring-Summer, p. 65-91.

(2) UNRWA does not have a proper budget and depends on contributions renewed annually. This structural weakness gives a greater role to its communication.

(3) The USA has been giving since 1950 more than 60% of its budget followed by the UK, and today by the European Community which became its second main contributor. The Arab countries are also key financial backers. In the 50’s and the 60’s, the US and Great Britain were providing the Agency with 90% of its budget.

(4) We worked mainly on a sample of these pictures and on the UNRWA Photo Catalogue made at the beginning of the 80’s (it is not precisely dated) by the UNRWA Public Information Division in Vienna. This paper is more broadly based on UNRWA audiovisual archives and on interviews with former photographers, filmmakers and employees of the public information office.

(5) United Nations Relief for Palestine Refugees.

(6) International Committee of the Red Cross.

(7) Letter from Charles R. Read, Field Director, to Bronson Clark, Palestine Desk, 4th November, 1949/AFSC Archives.

(8) Letter from Mr. Evans to Mr. Stanton Griffis, 26th December 1948/AFSC Archives.

(9) For a detailed study on the representations of the Palestinian refugees through humanitarian images (those of the Quakers, the Red Cross and the UNRWA). See Latte Abdallah, S., 2005, “La part des absents. Les images en creux des réfugiés palestiniens”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), 2005, Images aux frontières. Représentations et constructions sociales et politiques. Palestine, Jordanie 1948-2000, Beyrouth, IFPO, p. 67-102 ; Latte abdallah, S., 2007, op. cit.

(10) Interview, Amman, 15th February 2004.

(11) Interview, Beirut, 1st March 2004.

(12) Interview, R.W., former deputy director (1979-1998) of the Press Information Department of UNRWA, Amman, 18th February 2004.

(13) Idem.

(14) Beirut, 3rd March 2004.

(15) Till the new writing of the 1948 foundation war by the “new Israeli historians” since the 1980’s, namely Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, and Tom Segev and others.

(16) Ibid., p. 135.

(17) Barthes, R., 1980, La chambre Claire. Note sur la Photographie, Éditions de l’Étoile/Gallimard/Seuil, p. 133.

(18) Ibid., p. 138.

(19) Ibid., p. 131.

(20) Barthes, R., 1957, Mythologies, Paris, Gallimard.

(21) For more details, see Latte Abdallah, S., 2005, op. cit.

(22) ICRC, 1950.

(23) UN, 1950.

(24) See for instance UNRWA, Tomorrow Begins Today, pre-1967. These representations are also spread by the National Geographic Magazine between 1948 and 1967 as Annelies Moors has studied it. See 2005, “Framing the ‘Refugee Question’: the National Geographic Magazine 1948-1967”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), op. cit., p. 43-59.

(25) See as an example UNRWA, The Silver Lining, 1964.

(26) See UNRWA, A Journey to Understanding, 1961; UNRWA, Tomorrow Begins Today, pre-1967; UNRWA, The Silver Lining, 1964 or UNRWA, Flowers of Ramallah, 1963.

(27) See Latte Abdallah, S., 2005, “La part des absents. Les images en creux des réfugiés palestiniens”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), op. cit., p. 67-102.

(28) Colleyn, J.-P., 2005, “L’analyse des images d’archives : point de vue théorique et étude d’un cas”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), op. cit., p. 31.

(29) See The Palestinians, 1973-74; The Palestinians do have rights. The Question of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People, 1979; Refugee Visiting Abandoned Home in 1948, 1987.

(30) Like for instance Palestinian Portraits, 1987.

(31) See Culture/heritage, 1990; Palestinian Embroidery, 1990.

(32) G. N., Vienna, 27th April 2004.

(33) Barthes, R., op. cit., p. 90.

(34) Malkki, L., 1995, Purity and Exile. Violence, Memory and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania, Chicago/London, The University of Chicago Press, p. 9.

(35) Malkki L, op. cit., p. 12.

(36) Malkki L., op. cit., p. 11-12.

(37) Badiou, A., 1993, L’éthique. Essai sur la conscience du mal, Paris, Hatier.

(38) Barthes, R., p. 148-150.

(39) Ibid., p. 131.

(40) According to the listing of UNRWA films made by the UNRWA HQ in Gaza.

(41) UNRWA, 1983/1984 (not precisely dated), UNRWA Photo Catalogue, UNRWA Public Information Division, Vienna.

(42) Chevrier, J.-F., 1997, “L’intimité territoriale”, in Ceux du terrain, Ne pas plier, Ivry-sur-Seine, p. 33-51.

Bibliography

*Audiovisual archives:

– Photographic archives of the American Friends Service Committee Palestine 1948-1950

– Photographic archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross Palestine 1948-1950

– Photographic archives of the League of the National Societies of the Red Cross Palestine 1948-1950

– Audiovisual archives (stills and films) of UNRWA 1950-1998

– UNRWA, 1983/1984 (not precisely dated), UNRWA Photo Catalogue, UNRWA Public Information Division, Vienna.

– United Nations, Sands of Sorrow, 1950.

– ICRC, Les errants de Palestine, 1950.

– UNRWA, Tomorrow Begins Today, pre-1967.

– UNRWA, A Journey to Understanding, 1961.

– UNRWA, Beneath the Bells of Bethlehem, pre-1967

– UNRWA, Flowers of Ramallah, 1963.

– UNRWA, The Silver Lining, 1964.

– UNRWA, Aftermath, 1967.

– UNRWA, Peace is More than A Dream, 1973.

– UNRWA, Prelude to Peace, 1987.

*References:

Agamben, G., 1997, Homo Sacer, le pouvoir souverain et la vie nue, Seuil, Paris. Badiou, A., 1993, L’éthique. Essai sur la conscience du mal, Paris, Hatier.

Barthes, R., 1980, La chambre claire. Note sur la photographie, Paris, Éditions de l’Étoile/Gallimard/Le Seuil.

Chevrier, J.-F., 1997, “L’intimité territoriale”, in Ceux du terrain, Ne pas plier, Ivry-sur- Seine, p. 33-51.

Colleyn, J.-P., 2005, “L’analyse des images d’archives : point de vue théorique et étude d’un cas”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), 2005, Images aux frontières. Représentations et constructions sociales et politiques. Palestine, Jordanie 1948-2000, Beyrouth, IFPO , p. 25-36.

Fabian, J., 1983, Time and the Other. How Anthropology Makes its Objects, New York, Columbia University Press.

Farge, A., 2000, La chambre à deux lits et le cordonnier de Tel-Aviv, Paris, Le Seuil.

Harell-Bond, 1999, “The Experience of Refugees as Recipients of Aid”, in Ager, A., (ed.), Refugees. Perspectives on the Experience of Forced Migration, NY and London, The Tower Building, p. 136-168.

Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), 2005, Images aux frontières. Représentations et constructions sociales et politiques. Palestine, Jordanie 1948-2000, Beyrouth, IFPO.

Latte Abdallah, S., 2005, “La part des absents. Les images en creux des réfugiés palestiniens”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), 2005, Images aux frontières. Représentations et constructions sociales et politiques. Palestine, Jordanie 1948-2000, Beyrouth, IFPO, p. 67-102. Latte Abdallah, S., 2006, Femmes réfugiées palestiniennes, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France (translated in arabic : Lajiat min Falestin. Shakhsiat tabhath laha can tarikh, 2006, Beyrouth, Arab Scientific Publishers, Inc.)

Latte Abdallah, S., 2007, “Regards, visibilité historique et politique des images sur les réfugiés palestiniens depuis 1948”, in Le Mouvement social n° 219-220, Spring-Summer, p. 65-91.

Malkki, L., 1995, Purity and Exile. Violence, Memory and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania, Chicago/London, The University of Chicago Press.

Moors, A., 2005, “Framing the ‘Refugee Question’: the National Geographic Magazine 1948-1967”, in Latte Abdallah, S. (ed.), 2005, Images aux frontières. Représentations et constructions sociales et politiques. Palestine, Jordanie 1948-2000, Beyrouth, IFPO, p. 43-59. Zobeidi, S., 1999, My very Private Map of Palestine, documentary film.