The Arab College in Jerusalem, 1918-1948

The Arab College in Jerusalem, which was referred to as the Teachers’ Training Centre until 1927, played a significant role as a centre for education and culture. It nurtured numerous Palestinian figures, including authors, politicians, economists, and poets. Founded in 1918, it was led by prominent individuals such as educator and writer Khalil Sakakini, academic Khalil Totah, and educator Ahmad Sameh al-Khalidi.

The College continued to be the focal point for exceptionally talented students who aspired to enrol in it. To do so, they employed various strategies and means to excel and stand out, aiming to secure this opportunity because the College actively sought to attract only truly remarkable Palestinian students. Admission to the College was thus not limited to the affluent; it was accessible to both the poor and individuals from urban and rural backgrounds, including villagers and Bedouins. The Arab College maintained its status as a leading institution and educational facility for training Palestinian and Arab educators until the Nakba and the occupation of Palestine in 1948.

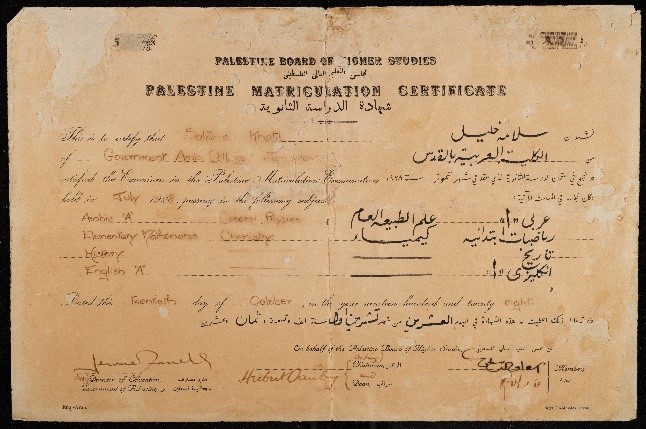

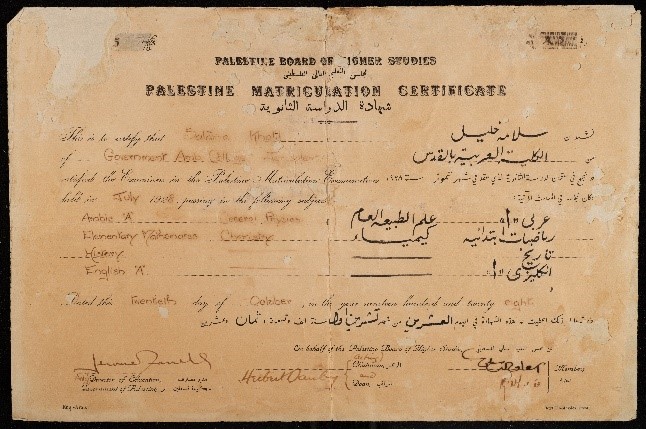

The year 1925 marked a significant milestone in the College’s history, thanks to a crucial judicial decision. This ruling mandated that the College should prepare students for the matriculation exam, which, in turn, enabled students to pursue further education beyond the borders of Palestine.

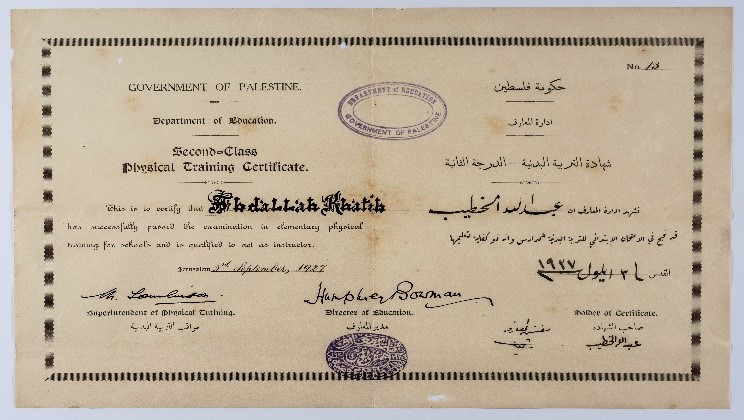

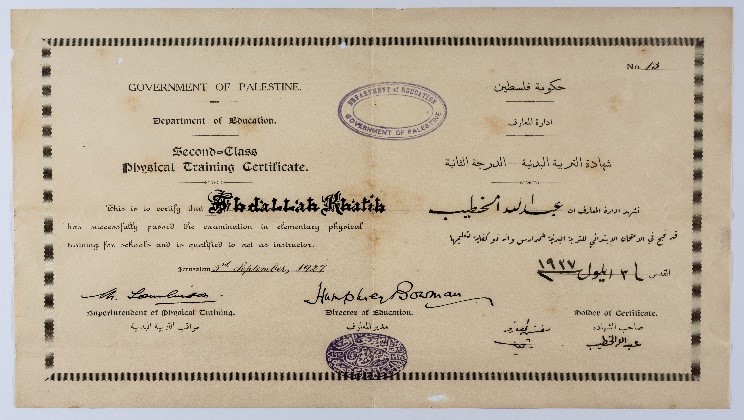

Following this pivotal ruling, the College shifted its focus to provide a diverse range of academic subjects. These included the Arabic and English languages, General History, Primary Mathematics, Geography, General Natural Sciences, and Chemistry. Additionally, the College introduced Physical Education as a primary subject, and it even granted certificates in Physical Education to schools.

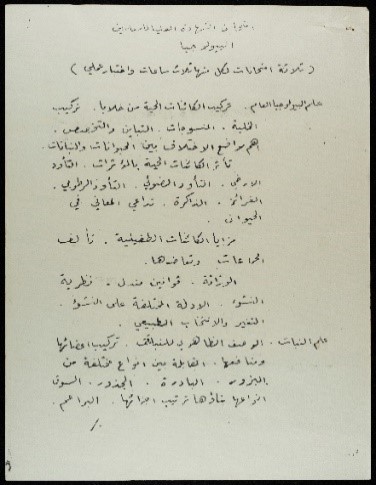

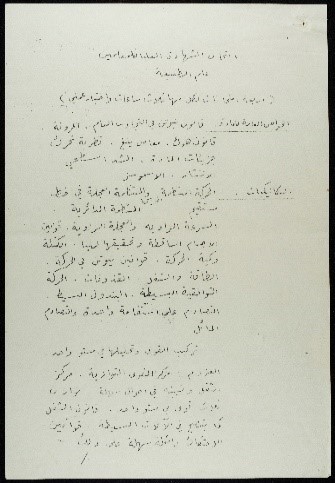

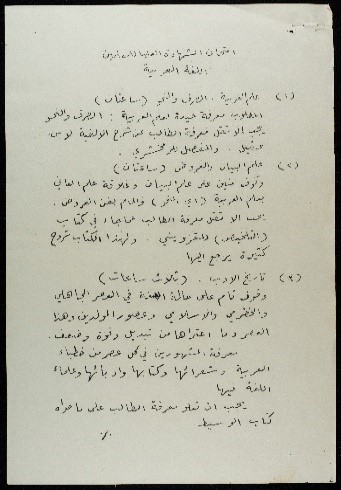

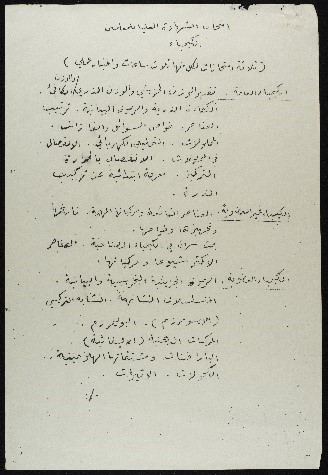

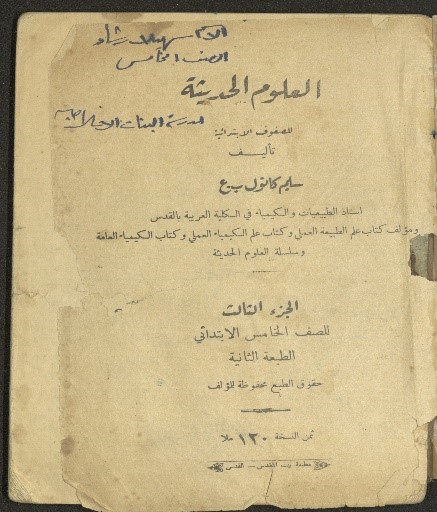

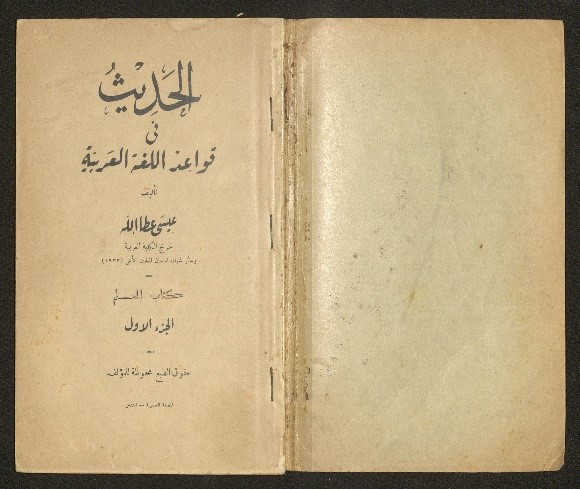

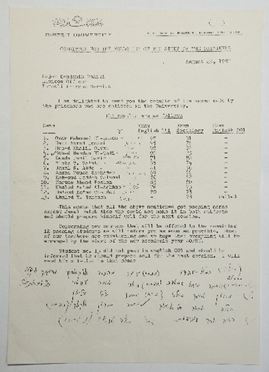

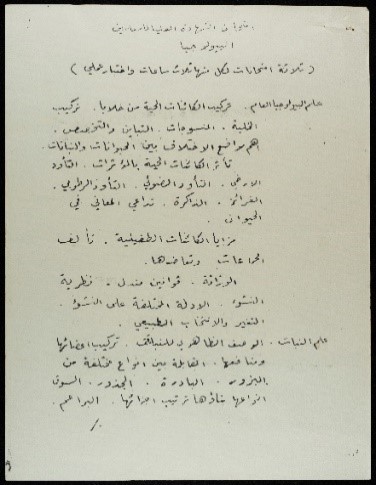

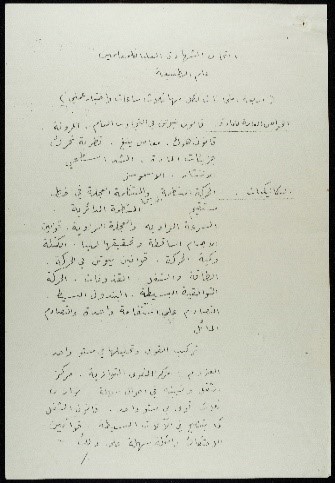

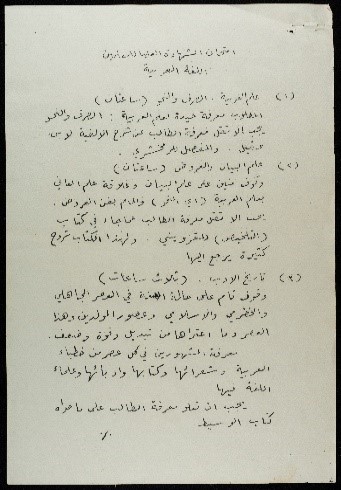

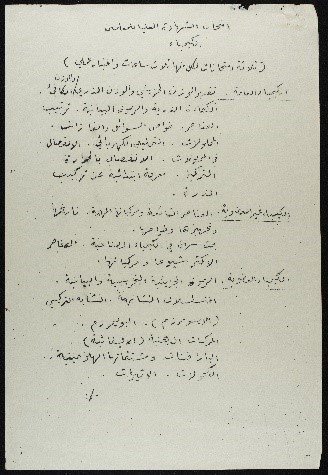

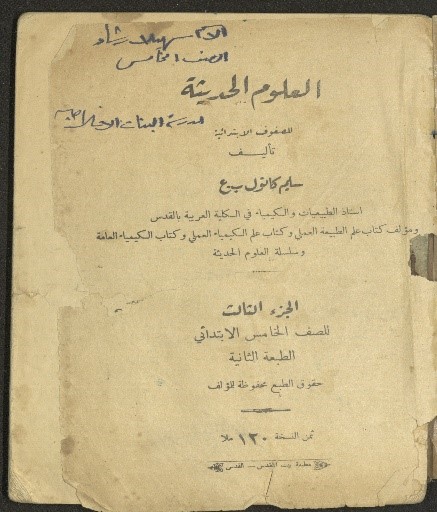

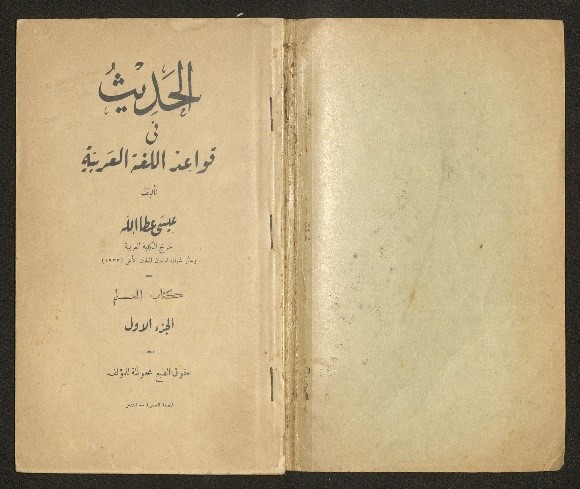

Examples of summaries by an Arab College student on the topics of the Arabic Language, Biology, Natural Sciences, and Chemistry, Sakher al-Khatib Collection.

The role of the College extended beyond its primary function as an educational institution for training teachers and students. It also made educational

contributions through its alumni, who actively participated in writing books used in the schools of the Education Directorate in Palestine. For instance, Saleem Konol, who served as a physics and chemistry teacher at the Arab College, authored the Modern Sciences textbooks for fifth-grade primary students. Similarly, Isa Atallah, a graduate of the College, penned a book for the era titled Speech in the Grammar of the Arabic Language that was specifically aimed at assisting Arabic language schoolteachers.

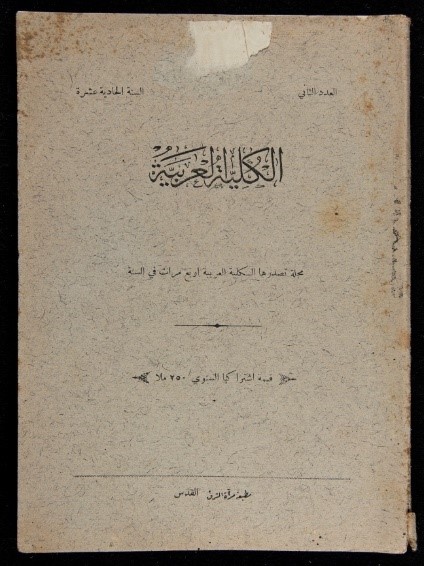

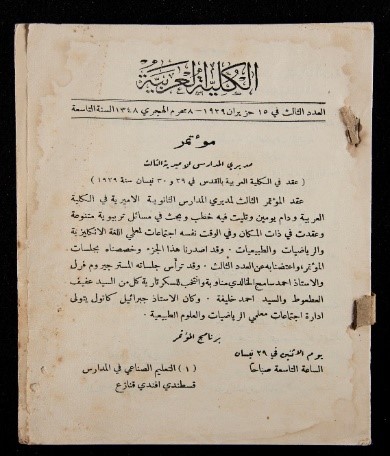

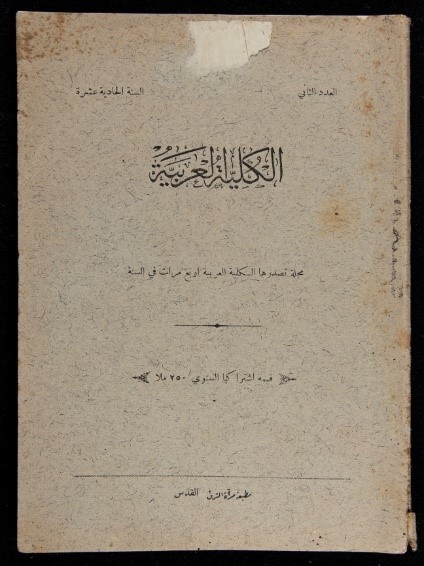

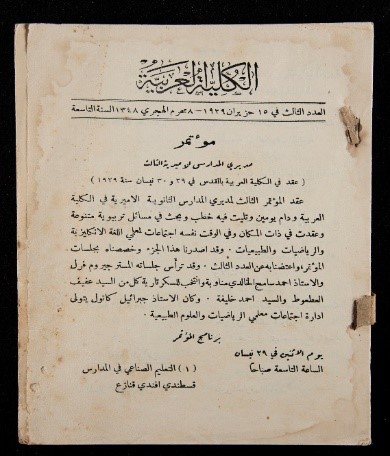

Cover of the second issue of the eleventh year of the Arab College Magazine issued on 1 March 1931. The magazine was printed at Mer’at ash-Sharq Press in occupied Jerusalem, and its annual subscription amounted to 250 mils.

In 1925, the College initiated a magazine bearing its name, with a primary focus on Educational Sciences. This publication was issued four times a year and featured updates on educational developments and covered conferences organised by the College.

The Arab College Magazine remained true to the College’s mission and consistently covered a wide range of topics of interest to its diverse readership, which included students, educators, and teachers. It stayed up to date with global scientific and educational advancements, highlighting significant accomplishments of Palestinian educators. The Magazine also had a strong commitment to advancing the educational and pedagogical landscape in Palestine, regularly featuring conference summaries and research contributions from its contributors. Within its pages, the magazine regularly showcased lists of its graduates and highlighted the College’s most noteworthy achievements. Unfortunately, the publication ceased when the College closed in the aftermath of the Nakba.

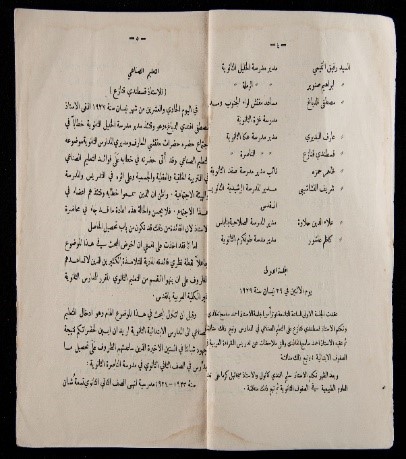

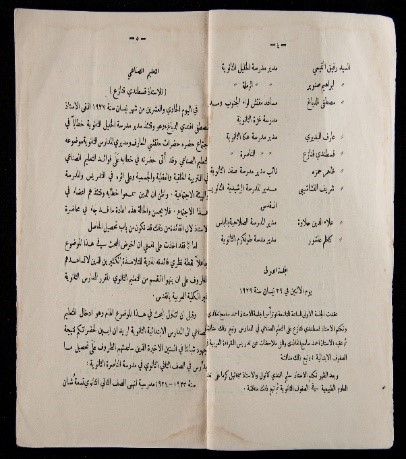

| For example, the Magazine’s third issue, released on 15 June 1929, was entirely dedicated to showcasing the programmes and research presented during the Third Princely School Principals’ Conference, which took place at the Arab College in Jerusalem on 29 and 30 April 1929. The event attracted the participation of several prominent Palestinian educators, including Ahmad Sameh al-Khalidi, Khalil Sakakini, Mustafa ad-Dabbagh, and Anis as-Saidawi, among others. | |

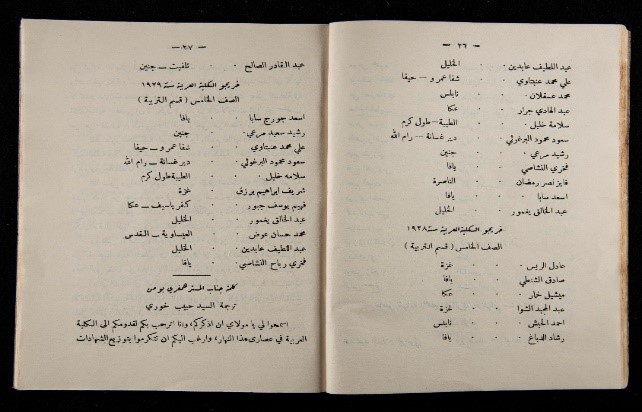

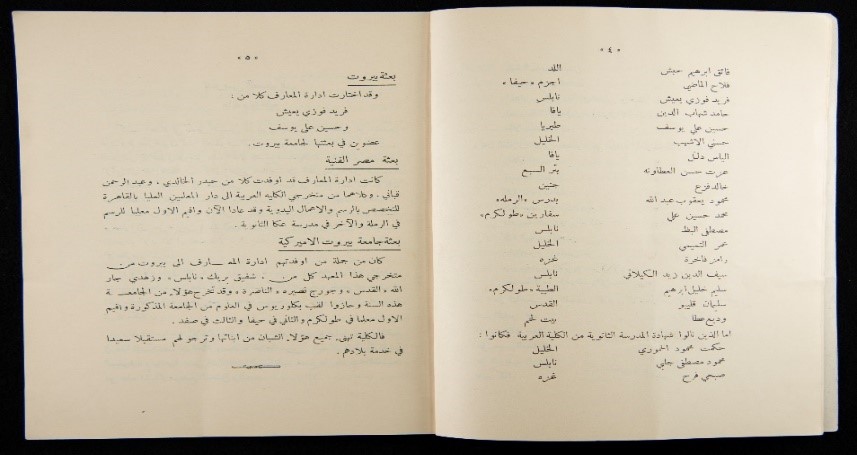

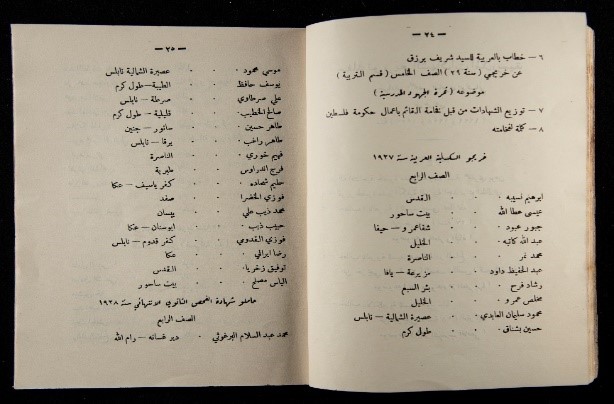

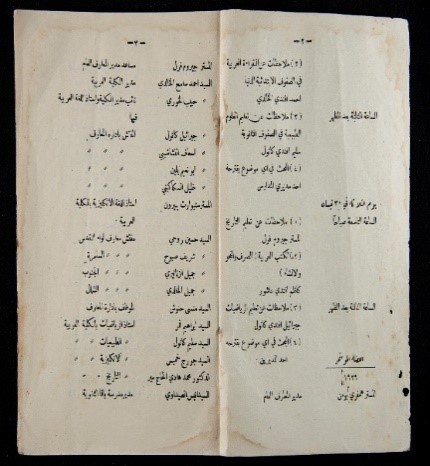

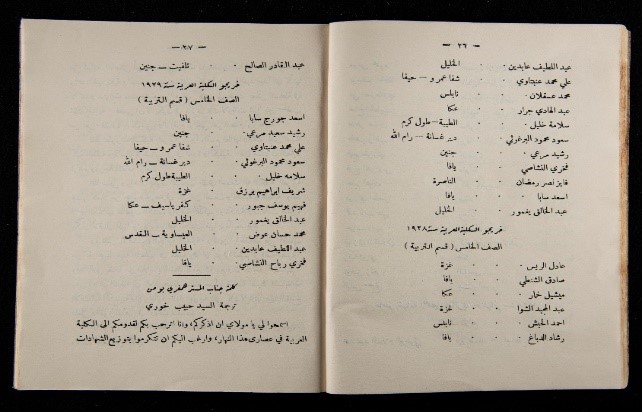

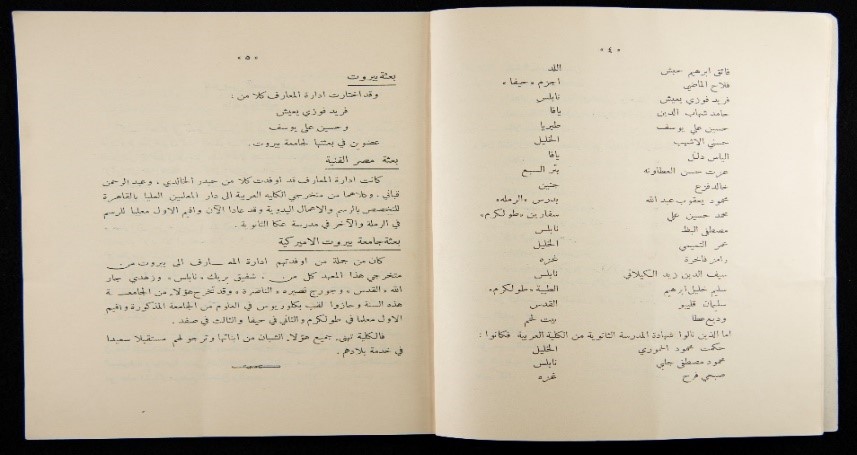

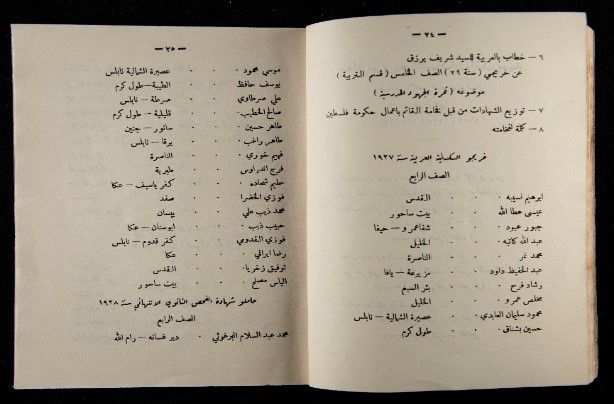

The magazine had a strong commitment to recognising the achievements of Arab College graduates. In the fourth issue of its ninth year, published in August 1929, it featured lists containing the names of College graduates from the years 1927, 1928, and 1929. These lists effectively showcased the diverse geographical and regional origins of the students, providing documentation of the cities and villages they hailed from. In the first issue of its third year, released on 15 December 1932, the magazine continued this tradition by publishing a list of the names of those who successfully passed the final secondary examination at the Arab College, which included the educator Husni al-Ashhab, who later became one of Palestine’s most influential educators. |

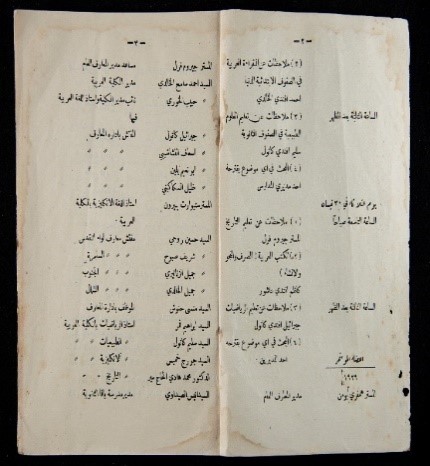

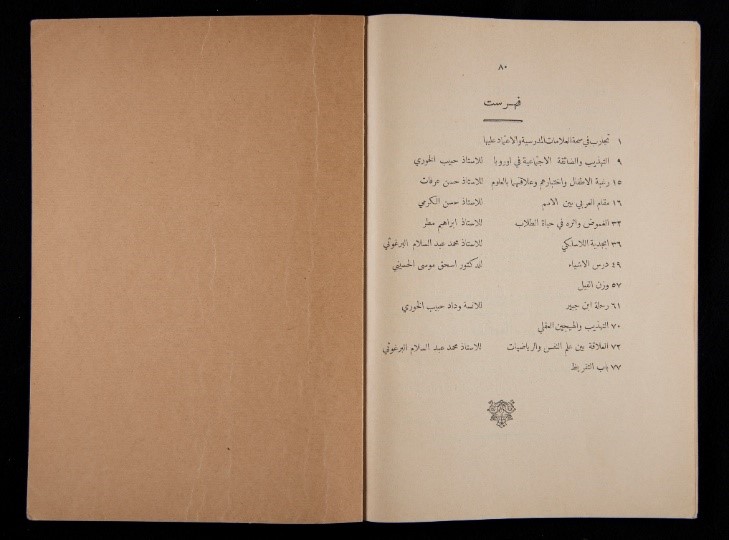

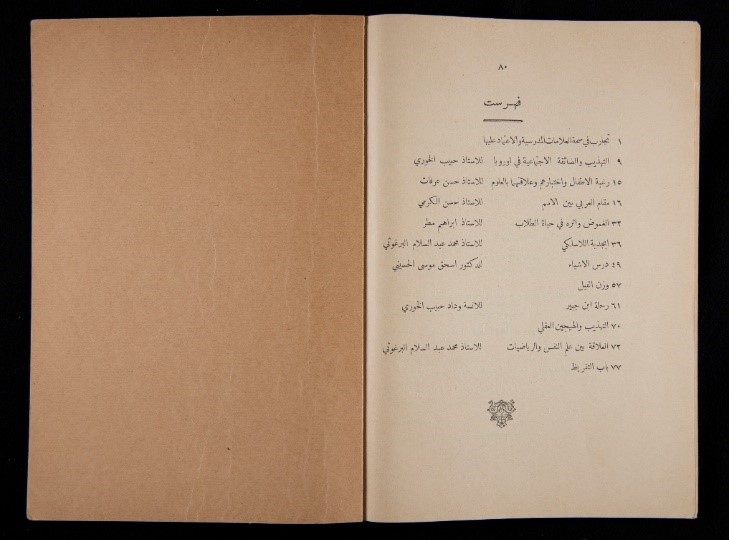

The Arab College Magazine covered a wide range of fields and topics, soliciting contributions from numerous educators. For instance, the index of the third issue of its eighteenth year, released on 21 May 1938, provides a glimpse of the diverse educational and scientific subjects featured in that edition. It also acknowledges the efforts of Palestinian educators, professors, and translators who contributed to its content. Some of the notable individuals involved in preparing these materials included Ishaq Musa al-Husseini, Ahmad al-Khalifa, Mohammad Abdel-Salam al-Barghouthi, Ibrahim Skaik, Habib al-Khoury, Hasan al-Karmi, and Hasan Arafat. Furthermore, this issue exemplifies the inclusion of women’s contributions to the magazine, featuring an article authored by Widad Habib al-Khoury.

This highlight aimed to provide insights into the Arab College and its Magazine by showcasing several documents that the Palestinian Museum Digital Archive (PMDA) team successfully accessed, collected, digitised, and archived. These materials are now available to the public on the PMDA website, offering a valuable celebration of one of Palestine’s significant scientific and educational institutions. The timing coincides with the beginning of the new academic year in Palestine at both the school and university levels.