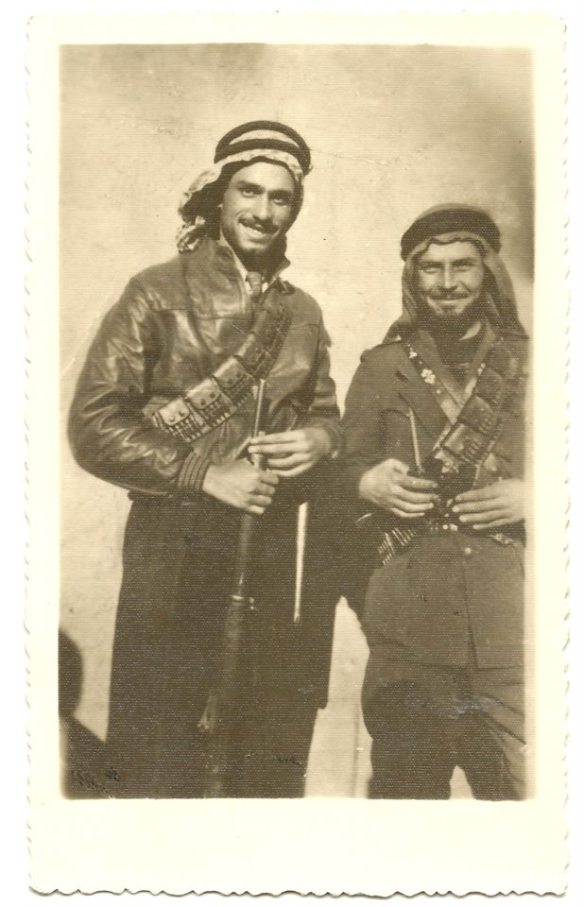

Rajih al-Salfeety, Sheikh of the Palestinian Zajjals

In the middle of a circle of women in the neighbourhood yard, Rajih al-Salfeety stands and performs songs, including special songs known as ahazij. His mother’s eyes go wide with pride whenever the women around her compliment her firstborn’s voice.

Al-Salfeety’s fate was to be born to a poor Palestinian family. It was also to lose his parents at a young age and step up to provide for his six siblings. Once a boy echoing his mother’s lullabies and signing in neighbourhood circles, with his beautiful voice, his joyful soul, and his good presence, he began singing at work, in his village, and at the surrounding villages’ weddings.

Rajih the Zajjal (a traditional oral strophic poet) grew like an olive seedling on the sides of al-Matwi and al-Sha’er valleys near the city of Salfit until he became the area’s best zajjal, even being mentioned in local sayings: ‘A wedding in Salfit is not a wedding unless Rajih is there’. He became known as the Sheikh of Palestinian Zajjals. Salfit, along with its troubles, continued to inspire him and lived within him, leading him to sing:

He who feels the troubles of people

If his emotions are described, becomes a poet

Oh, Paradise between Matwi and Sha’er

I would not trade you for the Heavens above

Al-Salfeety’s poetic conscience grew from the events taking place around him in Palestine, which affected his creations. Amongst those events were the al-Buraq Revolution and the 1929 execution of Muhammad Jamjoum, Atta al-Zeer, and Fouad Hijazi, three young men who participated and have since been immortalised in the famous popular song, Min Sijjin Akka (From Akka Prison). He was influenced by Nuh Ibrahim (to whom Min Sijjin Akka is commonly attributed), Ibrahim Tuqan, and other poets from that period.

Despite his young age and the great responsibilities entrusted to him, Al-Salfeety joined the ranks of the Great Palestinian Rebellion of 1936 and sang for and about it. He also volunteered in the war that broke out during the Nakba until he was severely injured by a bullet near his lungs; he later suffered from chronic lung diseases as a result.

As soon as the Nakba became the reality lived by Palestinians, and with the emergence of national and communist parties in Palestine, al-Salfeety became a part of the National Liberation League as one of its prominent freedom fighters and symbols. He was chased and imprisoned for it, especially since he was in opposition to the Baghdad Pact, as made clear by his derisions of the Pact in several poems.

During the 1950s, al-Salfeety snuck to Damascus and Baghdad and then Czechoslovakia, leaving Salfit and Palestine behind. He only returned to them during the early 1960s. He was made a fugitive again and left for Syria, returning to Palestine, at last, during the 1967 Naksa, never to leave again.

In the shadow of all this, al-Salfeety wrote about defeat, the Naksa, and settlements:

Oh, Naksa, day of misfortune, you will always remain a despicable witness

To the policy of annihilation and displacement

Even foxes roared at you

When no one useful was left standing

Rajih al-Salfeety lived an eventful life. He was arrested more than once, the first time in 1974 due to his patriotic activity, and the last time in 1988. In prison, he wrote several zajal poems, including ones he wrote in Nablus Central Prison, which other prisoners repeated, these words travelling from one prison to the next. Those poems included ‘In Memory of the Battle of Karameh; ‘In the Triumph of the Cambodian People’, ‘To My Son, Ahmad’, ‘In Memory of Ominous June’ and others.

In 1976, al-Salfeety decided to run for the elections of the Municipal Council in Salfit, where he established a national popular bloc with his comrade Khamis al-Hamad and several area notables. The bloc raised the unified slogan of all other national blocs in Palestine, which was ‘No to Civil Administration, Yes to National Unity.’ For the bloc, Rajih sang his chorus:

Oh, our popular masses

Oh, labour forces

Our national bloc

Aside from the bloc, we have nothing

Aside from the bloc, we have nothing

Rajih al-Salfeety had a notable presence at Birzeit University, where he participated several times in its annual festival and various activities. He sang more than once and made his zajal present in its corridors. When the university was forcibly closed, al-Salfeety sang:

The universities have been closed, where is democracy

The doors were closed, students are scattered

A state with tanks, fleets, and planes

How is it scared of drawings on withering paper?

(From an archived voice recording)

The notebooks written by Rajih al-Salfeety and his daughter Duha are nearly filled to the brim with poems praising stones, shuhada, the Intifada and Land Day. Al-Salfeety wrote tens of poems and chants, and he sang for the Intifada at weddings. His voice resonated loudly until the chorus, echoed by youth before the old mulberry tree in his village square, ‘stopping the awl’ (see poem below) of the Civilian Administration officer when he cornered them there.

He sang, inspired by al-Ashiqeen Ensemble:

Oh world, bear witness to us and the Gaza Strip

Bear witness to the West Bank

Demonstrations immersed deep in the conflict

Against the armies of Zionism

In early 1988, Rajih al-Salfeety wrote and sang one of the most important folkloric poems titled ‘El-Kaf Elly Byekser el-Makhraz’ (The Palm that can Stop an Awl) which spread widely and was popular among Palestinians due to its simplicity and depth of meaning. In it, he says:

Oh, voice, rise and call to those with determination

And leave those who found comfort in the allure of decadence

The news of massacres has echoed in the ears of nations

To shake their consciences and wake them up

He ended by writing:

We have learned much from our experience

Experiences are guiding beacons

The palm steady in the unity of class and determination

Can not only hit back against the awl of the treacherous

It will break the awl and the neck of its bearer

Al-Salfeety lived a long life of resistance and zajal, leading him to deservedly earn the sobriquet ‘Sheikh of Palestinian Zajjals’. His words resounded in many Palestinian rostrums in Nazareth, Haifa, Yaffa, Akka, Jerusalem, Ramallah, and Nablus, with renowned Palestinian writer Emile Habibi saying of him ‘I saw them holding a stone in one hand and the zajal of Rajih al-Salfeety in the other.’

The bullet al-Salfeety was shot with in 1948 haunted him for four decades, continuously affecting his health until he fell severely ill in 1990 and his nights felt longest: ‘Oh night-time, how long you are for those who are ill.’ This was one of the last poems he wrote before he passed away on the 27th of May 1990. His voice made its eternal departure from the world, leaving behind his four children, Yousra, Duha, Andaleeb, and Ahmad.

Al-Salfeety trotted between zajal verses like a stag in the Palestinian wilderness, to sing with a reed pipe player or a drummer; together they would produce a truly Palestinian tone. Behind them, the voices of the Palestinian villages’ youth would repeat the chorus of national unity with enthusiasm, making him stop them and jokingly say: ‘Listen, kids, if you keep jumping around and hurrying everything you will ruin the evening gathering for us. Overenthusiasm is more harmful than a gun.’